- Climate Change and the Mising tribe:

Climate change is real and is already taking place. The report of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that “Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, as is now evident from observations of air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice, and rising global average sea level” (IPCC 2007). Similarly, patterns and amounts of precipitation are also likely to change, and it is projected that rainfall will increase in some areas and decrease in others (IPCC 1996, IPCC 2014). The meteorological impact of climate change can be divided into two distinct drivers; climate processes such as sea-level rise, salinization of agricultural land, desertification and growing water scarcity, and climate events such as flooding, storms and glacial lake outburst floods. Similarly, non-climate drivers, such as government policy, population growth and community-level resilience to natural disasters, are also important. All these contribute to the degree of vulnerability[1] people experience(Brown 2008). The impacts of climate change and their associated costs will fall disproportionately on developing countries threatening to undermine the achievement of sustainable development goals, reduce poverty, and safeguard food security. Further, the impacts of climate change are likely to increase the rate of migration of agriculture-dependent rural communities in search of livelihood opportunities. The high rate of poverty, population growth, limited landholding size, limited livelihood opportunities combined with climate change have increased forced migration in the developing countries. The IPCC report of 1990 has stated that by 2050, an estimated 150 million people could be displaced due to climate-induced factors like floods, drought or storms. According to a report published by International Organization for Migration (IOM), forced migration increases pressure on urban infrastructure and services, undermines economic growth, increases the risk of conflict thereby leading to low human development among the migrants.

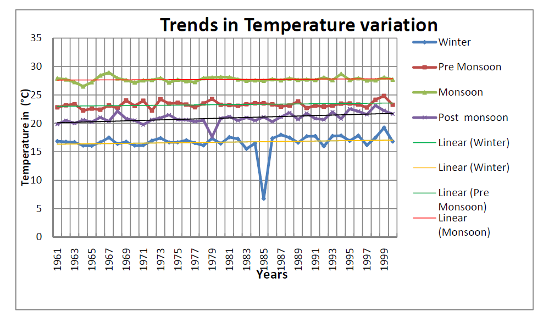

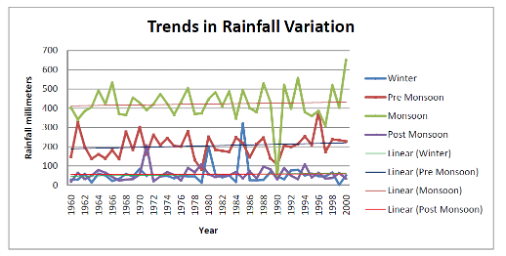

The Mising tribe with a population of 680424 (Census of India 2011) are mostly inhabited in the riverine areas of northern and southern banks of river Brahmaputra in Upper Assam. It falls in North Bank Plains and Upper Brahmaputra Valley agro-economic zone. The average rainfall of 1000 to 2000 mm per year characterizes the region; fifty percent of total rainfall is during the monsoon season. It is high humidity (more than 80 % relative humidity). The temperature in the region ranges from 7 to 37 Degree Celsius. The soil varies from acidic, neutral to less acidic in the three belts of the zone descending from the foothills to the river bank. Sali, Ahu, and Boro are the three main varieties of rice commonly grown among the Mising. Similarly, the commonly grown pulses are Matimah (Phaseolus mango), Magumah (Phaseolus aureus), Arhar (Cajanus cajan), Masurmah (Pisum sativum) (Assam Agricultural University 2011, ICAR 2011). There are impacts of climate change in the region in terms of changes in temperature and rainfall patterns. For instance, the analysis of meteorological data provided by the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) (Dibrugarh and Jorhat station) for the period 1960 to 2000 for temperature shows that the temperature has risen in three seasons, namely post-monsoon, winter, and pre-monsoon to a varying extent (Fig 1). Similarly, the rainfall data for the period 1960-2000 and 2005-2009 shows that there is an increase of rainfall during monsoon though it decreased during the period 1971-1990 while during winter, pre-monsoon and post-monsoon rainfall has decreased during the last few decades (Fig 2).

Figure 1: Trends in temperature variation from 1960 to 2000

Fig 2: Trends in rainfall variation from 1960 to 2000

The impacts of climate change and climate extremes such as floods, erosion, occasional drought, etc., have been felt among the Mising tribes with continuous shifts in rainfall patterns as well as changes in the temperature. Although they have been adapting since generations, of late they are on the brink of becoming climate refugees due to repeated flooding and erosion(Pegu and Pegu 2018). Low education, limited livelihood options, poor access to modern services, and inequitable access to productive resources among the Mising reduce the communities’ capacity to cope with climate-related natural disasters. Further high dependent on the climate-sensitive agricultural sector (83.7% as per the census of India 2011) makes them highly vulnerable to climate change.

- Climate Change Adaptation among the Mising tribe

Adaptation[2] to climate change is important in response to the accelerated impacts of climate change. Adaptation varies across countries, societies, communities, and even within the household. The Mising had undertaken short term structural measures (Stilt House, High raised platform, Country boats, Banana rafts, bamboo rafts, High raised platforms/ embankments) as well as non-structural (Migration, Change in cropping pattern, Relief, and Relief camp) measures to adapt to climate extremes(Katyaini.S, A et al. 2012). For instance, the introduction of Boro[3] rice, cultivated in waterlogged, low-lying or medium lands with irrigation from November to May have benefitted the communities residing in flood zone (Singh 2002). Similarly, traditional institutions, as well as indigenous knowledge in the past, played a significant role by making the communities less vulnerable to uncertainties posed by floods(Barua et al. 2014). However, in recent times, climate change has accelerated, and the traditional social institutions and indigenous knowledge systems have started to erode. For example, there has been a gradual loss of ecosystem and biodiversity-related knowledge, traditional agricultural practices among the Mising tribe. Recent trends show migrations among youths (within the State as well outside the State) have been considered as an alternative way of adapting to increased flood in the region. A rough estimate of above 50000 youths are said to be working outside the State in search of better livelihood opportunities. The youths mostly migrate to States like Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Maharashtra to seek employment opportunities as unskilled laborers. They mostly work as security guards, laborers in industries, waiters, etc. Lack of job opportunities, employment diversification, poverty, and vulnerability of livelihood to frequent floods and occasional drought are the main reasons for people migrating to other places.

Is migration the best options of adaptation to climate change among the Mising tribe? There have been various views regarding the impacts of migration. Migration hinders development by increasing pressure on urban infrastructure and service, increasing risk of conflict and leading to worse health, poor living conditions and other social indicators among migrants(IOM 2008). Temporary migration as an adaptive response to climate stress is already apparent among the Mising. Migration may have negative impacts on the communities. Tribal communities who are mainly dependent on natural resource-based livelihood are likely to lose the skills in farming. Further, migration is leading to a decrease in the workforce among the Mising society. The youths are no longer interested in agriculture due to unpredictability in production, low profitability, and risk to floods and occasional drought. The migrant are also likely to face the impacts of ethnic violence as seen in the recent exodus of migrant workers from North East India in Bangalore. There are also reports of high school dropouts due to migration. Further, the migrants are also likely to miss out on the benefits of government schemes implemented in the region. For instance, there are reports of exclusion of names from the list of NRC in Assam. Along with these, a range of socio-economic problems is likely to arise such as poor living conditions, poor health, limited social networks, etc., among the Migrant Mising youths.

- Enhancing adaptation among the Mising tribe

Enhancing adaptation among communities to climate change would require improvements in education, livelihood diversification and accessibility to Government interventions & schemes (IPCC 2014). Therefore, the following section discusses the status of education among the Mising and its issues, the opportunities for livelihood diversification and initiatives undertaken by Government in Mising inhabited areas. It attempts to unearth the underlying factors leading to low education, reasons for limited livelihood diversification, and failure in Government interventions.

Educations: Educations plays a crucial role in building adaptation. There are many reasons for making investments in education evidenced by the abundant climate change literature showing that better-educated people tend to have higher adaptive capacity[4] (Adger et al., 2004, Wamsler et al., 2012; Land and Hummel 2013, Striessing, Lutz, et al. 2013). Researchers have further agreed that the most effective long-term defense against the adverse impacts of climate change is strengthening the factors associated with enhancing human capital. Education can strengthen human capital because it is linked with improving health, eradicating extreme poverty, and reducing population growth. Further, studies show that an educated society is more empowered and more adapted to recover from climate change-related natural disasters (Brink 2010, Wamsler, Brink, et al. 2012).

Low educations have hindered adaptation amongst the Mising. Although the literacy rate of the Mising is 69.3%(Census of India 2011), a high rate of dropout is a concern. Lack of quality education, economic compulsion, and social issues such as early marriage are the contributing factors towards high school dropout rates among the Mising. Despite initiatives by the Government, they have failed to take actual benefits from such schemes. Low educational attainments have resulted in a high rate of unemployment, high dependency on climate-sensitive agriculture, as well a high rate of migration amongst the youth. Further, lower educational attainments among the communities have limited their awareness and participation in the Government interventions. Therefore, there is an urgent need for improving the overall education scenario in Mising inhabited areas. There are reports of poor quality (teacher-pupil ratio in a class), low availability (school: primary and below, middle, secondary, higher secondary; college: bachelors and above), and accessibly (lack of income to access higher education). For instance, the average student-teacher ratio is reported to be 50:1 or just one or two teachers in most of the primary schools. This hinders the quality of education. Similarly, accessibility to higher education is a concern due to the high rate of poverty. Improvements in these indicators will be crucial for building adaptation among the Mising.

Livelihood diversification: Diversification of income sources is considered to be an important aspect of enhancing adaptation to climate change (Adger 1999, Kelly and Adger 2000, Yohe and Tol 2002, UNDP 2009). As farming is a seasonal occupation, livelihood diversification supplements farm incomes. The livelihood diversifications to include less climate-sensitive occupations such as poultry, livestock, fisheries, small-scale business or industries are important.

The Mising are mostly dependent on agriculture, which is yet to be modernized. A decrease in agriculture production in Mising inhabited areas have been reported due to unseasonal rainfall, and pests and disease outbreak (ICAR 2015). As such, there is an urgent need for diversification of livelihoods among the Mising. Currently, their only source of income apart from agriculture is working as unskilled laborers under MGNREGA. However, there are reports of a delay in payments of wages under MGNREGA schemes. Employment diversification in the form of poultry, dairy farming, piggery, fisheries, setting up of handloom industries, eco-tourism, sustainable form of agriculture, self-help groups, etc., will be crucial among the Mising for future adaptation to climate change.

Accessibility, Transparency, and Accountability to Government Schemes: Accessibility to Government schemes and support are crucial during unexpected occurrence climate extremes such as floods, drought, etc., (Barua et al., 2014; Katyaini, et al. 2012). The Central as well State Government has implemented various government schemes. Some of the schemes implemented in Mising inhabited areas are on agriculture (KCC, PMFBY), housing (PMAY), sanitation, MGNREGA, food security, etc(Table 1). These interventions aim to enhance overall human development by improving the level of education, food security, health, gender equality, etc. and thus enhance their capacity to adapt to any unforeseen event in the future including climate change.

| Sl. No. | Sectors | Interventions (schemes and programs) | The focus of these interventions | |

| 1. | Farm | 1. National Food Security Mission 2007 (Government of India 2007)Kishan Credit CardPradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana – Crop Insurance | Aims to lunch a food security mission comprising rice, wheat, and pulses to increase the productionCrop insurance | |

| 2. | Non-farm/employment | 1. Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA)(Government of India 2015) | 1. To guarantee rural employment and provide a minimum of 100 days of work | |

| 3. | Health and healthcare | 1. National Health Mission 2013 (Government of India 2013) | Health service beyond reproduction and child health addresses the issues of communicable and non-communicable diseases. Also aims to improve infrastructure | |

| 4. | Food and Nutrition Security | 1. National Food Security Mission (Government of India 2007) | Aims to lunch a food security mission comprising rice, wheat, and pulses to increase the production | |

| 5. | Gender and social equality | 1. Reservation in education, health, and other government schemes (Government of Sikkim 2014) | To encourage equal participation in education, health, and other social sectors | |

| 6. | Sanitation and hygiene | 1. Total Sanitation Campaign/ Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan/Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Government of India 2012) | Accelerate sanitation coverage in rural areas | |

| 7. | Housing and energy | 1. Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana-Gramin (Government of India 2014) | 1. Provides financial assistance to the rural poor living Below the Poverty Line | |

Table 1: Government Schemes implemented in Mising inhabited areas

Despite these initiatives by the Government, very few people have benefitted from such schemes. Lack of accessibility, transparency, and accountability of schemes implemented are reported in the community. Further, lack of awareness and access to sufficient information is a concern.

Therefore, a possible method to enhance their adaptive capacity of the Mising Community is to encourage education, promote alternative employment opportunities, invest in better methods to prevent the loss from frequent floods, and ensure that the intended (poorest) section of the population benefits from the government schemes.

Reference:

Assam Agricultural University (2011). ” Agro-climatic zones of Assam.” 2019, from http://www.aau.ac.in/dee/annexture6.php.

Brown, O. (2008). Migration and Climate Change. Geneva, International Organization for Migration.

Census of India (2011). Census of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

Government of India (2013). “National Health Mission.” Retrieved 12 Aug 2017, from www.nhm.gov/nhm/about-nhm.html.

Government of India (2014). “Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana-Gramin.” Retrieved 18 July, 2017, from www.pmayg.nic.in/netiay/about-us.aspx.

Government of India (2007). “National Food Security Mission.” Retrieved 01 May 2017, from www.nfsm.gov.in.

Department of Drinking Water Supply

Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission.

Government of India (2015) The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005.

ICAR (2011). “Agro-climatic zones of Assam.” 2019, from http://www.rkmp.co.in/content/agro-climatic-zonesof-assam.

ICAR (2015). Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Lakhimpur. Krishi Vigyan Kendra.

IOM (2008). Migration and Climate Change. Geneva, International Organization for Migration.

[1] Vulnerability is the degree to which a system is susceptible to and unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change, including climate variability and extremes.

[2]Adaptation refers to adjustments in ecological, social, or economic systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli and their effects or impacts. It refers to changes in processes, practices, and structures to moderate potential damages or to benefit from opportunities associated with climate change.

[3] “Boro” is a Bengali language word derived from a Sanskrit word “BOROB”. This means a special type of rice cultivation on residual or stored water in low-lying areas after the harvest of Kharif rice.

[4] Adaptive capacity relates to the capacity of systems, institutions, humans and other organisms to adjust to potential damage, to take advantage of opportunities, or to respond to consequences. In the context of ecological systems

Be First to Comment